212. Recruiting the Hero of Two Worlds with Mike Duncan

To kick off Season 6, we bring you the story of America’s Favorite Fighting Frenchmen.

In 1777, the Marquis de Lafayette sailed from France with a commission as a major general in the Continental Army. Unlike many other European soldiers of fortune, Lafayette paid his own way and had no expectation that he would be placed at the head of American forces.

We best remember Lafayette for his service in the American Revolution, his close relationship with George Washington, and the key to the Bastille that now hangs in the main entrance to Washington’s Mount Vernon.

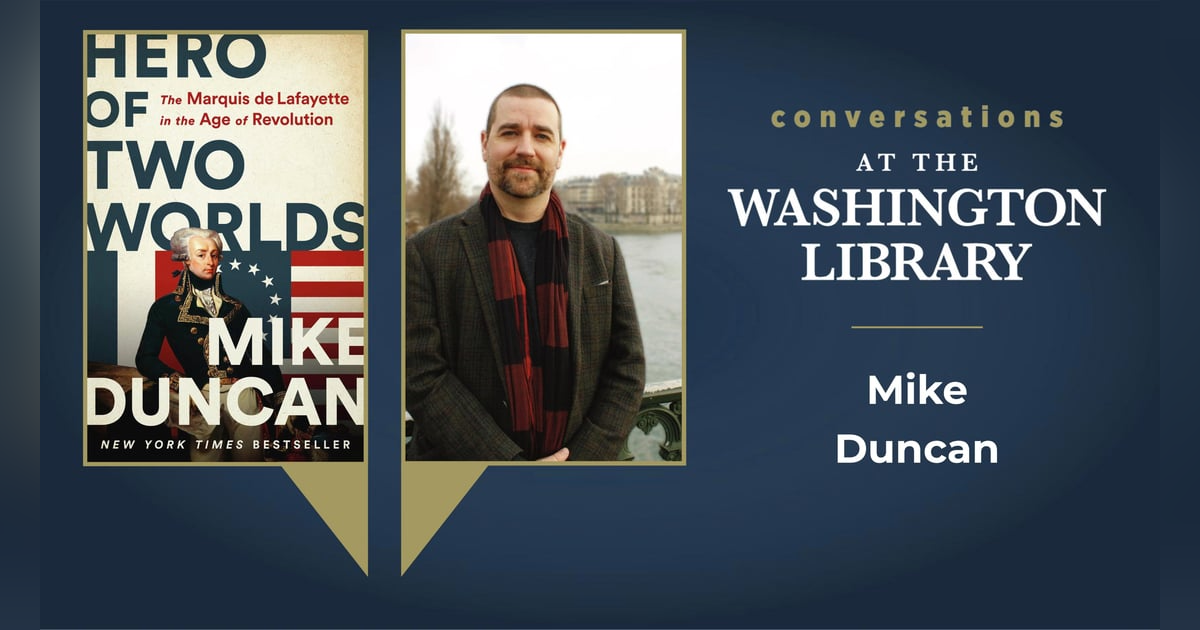

But Lafayette was more than meets the eye. On today’s show, podcasting legend and author Mike Duncan joins Jim Ambuske to discuss his new book, Hero of Two Worlds: The Marquis de Lafayette in the Age of Revolution, published by PublicAffairs Books in 2021.

(Be sure to check out a map of the Battle of Monmouth over on our blog).

You may know Duncan from his two podcasts, The History of Rome and Revolutions, and in his latest book, he tackles a complex man who was at the center of the Age of Democratic Revolutions.

It’s great to be back with you; we have a great season ahead of us, and we have a brand new segment in which our guests talk about the work that inspires them.

Recruiting the Hero of Two Worlds with Mike Duncan

Interview published: October 6, 2021

Transcript created: October 11, 2021

Host: Jim Ambuske, Center for Digital History, Washington Library at Mount Vernon

Guest: Mike Duncan, author.

Note: This transcript was produced using Descript, an artificial intelligence software. It has been edited to correct errors in the transcription, such as names, but has not been subject to significant clean up.

Jim Ambuske: Mike, I'm delighted to have you here. Thank you very much for joining us. I've uh, I've been following your work for a long time, especially since the history of Rome podcast. And I hope we can talk a little bit about your podcast work later on over the course of our conversation. Lafayette, the Marquis de Lafayette is seemingly everywhere these days.

It seems, especially in our ears as a consequence of Hamilton and David Diggs' interpretation of him and here at Mount Vernon, of course you were here just a couple of weeks ago, filming a segment for CBS this morning, and you saw the best deal key, which Lafayette gives to wash. But it's my sense. And I don't know what you think.

It's my sense that we really don't know much about Lafayette beyond one, his service in the American revolution, uh, to the bass steel key, which connects him to the French revolution. And in many ways, that's about all we get. What are your thoughts on that?

Mike Duncan: I would definitely agree with that. The only thing I would add is that there is.

Awareness, usually at the local level of Lafayette's returned to her in 1824 and 1825, because that's where and why there's a Lafayette, something in practically, every city and state and county in the United States, because he visited all of the, I think it was 30 states that existed at the time of that tour.

So basically everything east of the Mississippi. So that's, that's really the only other thing that I would like add to that as, as what do we know about LA. And yeah, when you come across him for the first time, he is very much treated as a sort of like if you look at the American revolution is a great piece of drama that we, a story that we tell ourselves about our founding.

There are main characters, there are main characters like George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin. You know, these guys are, they're gonna to. In the credits, right? And then there are recurring characters, uh, usually a little bit colorful. Uh, sometimes we bring them in for foreign spice.

We've got Baron Von Steuben, you know, we got Baron to cow, we've got to Cusco. And then of course Lafayette is I think probably the most famous of these sort of. Foreign characters who come into the mix because of, he was so closely connected to George Washington. They did really have a personal intimate friendship and intimate relationship.

And he was a great friend to the United States all through his life. But as you say, he comes over here is like a 19 year old he's serving in the continental army in his early twenties. This is the Lafayette that we know and think about. This is young Lafayette. But he lives until 1834. You know, he dies at, in his mid seventies.

He does not just disappear from the historical stage. And so what I'm trying to do in hero of two worlds is to expand the entire story of this guy's life. Because when I was doing the revolutions. The thing that I discovered is that yes, he shows up as this 19 year old in the continental army. And then as I move forward through the French revolution, the Haitian revolution, Spanish American independence, though the revolution of 1830 Lafayette just keeps appearing and reappearing and reappearing.

He never really retired. In any, in any formal sense of the word, he had a period during the Napoleonic empire where him and Napoleon Bonaparte, who he also had a personal relationship with. It was just quite a bit more combative than his relationship with Washington. Lafayette is a politician and a leader and a revolutionary and a reformer for his entire life.

And that's what Hero of two worlds is attempting to do is bring this sort of person who has been treated as a side character and bring him to the fore and say, let's talk about his point of view. Let's talk about his, uh, his life experiences because he experienced so much. In the rooms for some of the most important things that have happened in the history of the Atlantic world.

And then just sort of the history of the modern world in general. So was it when you were doing your revolutions podcast that you first encountered this guy and thought there might be something more here to do. Yeah, absolutely. Because I, you know, as you just said, I don't think I was any different from the average American when it comes to, you know, what do I know about this guy?

I knew when I was writing my series on the American revolution, that I would immediately be following it with a long series on the French revolution. And so, while I was writing the American series, I did pay some special attention to the people who I knew would show up in the French revolution. The two most important of them being, uh, the marquee Dolores.

And then also Tom Paine, right? Tom Paine is also somebody who moves from one revolution to the next and plays a role in both of them. So I paid a little special attention to them. And then when I got to the French revolution, I'm talking about Lafayette and he sent the key of the, of the Bastille to George Washington.

But, how does he into possession of it. And it turns out that it's because he was an integral player in the reform movements of the 1780s that then culminate with what becomes the French revolution of 1789. He used then an inner circle. One of the most influential figures in the revolution, not just in 1789, but also 1790 in 1791.

There's a there's a a good three-year period in the French revolution where Lafayette is amongst the most famous and most influential revolutionaries. And the thing that happens to him in, in historical memories, then of course, the revolution keeps radical. And he's [00:05:00] amongst also then the Mo one of the famous people who get ousted from the revolution as the revolution radicalizes and he is overshadowed by people who became his political enemies, like Robespierre and Denton and Dan Milan Murrah.

When those guys come to power, Lafayette's got no place in the revolution anymore. And he gets, he gets bounced out the other side. And then from my point, At this point to, you know, to get back to the original question is I think, okay, that's it for Lafayette he's done. And then I know later he comes back for this American tour that like, obviously he's been in retirement for 30 years, probably just trying to lay low.

And like, that's not the case at all. He spent he, well, first he spends five years in an Austrian dungeon. Then he comes back and he's all combative with, uh, with Napoleon Bonaparte who he knows personally. And then he's a deputy in the French chamber of deputies. He's involved in secret underground carbon, Ari conspiracies to overthrow Louis the 18th.

And then he's an integral part of the revolution of 1830. He's essentially the reason why the revolution of 1830 goes the way that it does. I'm like now he's 70. I cannot, I cannot get rid of this guy. He, he will not stop showing up. You know, he's like, he's like a, he's like a stray dog that won't go away.

So when I got to the end of all this I'm I'm I was about at the revolution of 1830 in the show when my first book came out and did well. And then the publisher is like, what would you like to do next? And I was like, I want to write a biography of Lafayette. I want to go back and start with this guy from the beginning.

And retrace my steps through everything that I've covered in the show, the sort of grand age of democratic revolution with this guy, who's going to be there for everything sort of being our window into.

Jim Ambuske: I love that concept. And as you know, the title of your book is hero of two worlds and he experiences these two revolutions in which republicanism is trying to find its place in the Atlantic world.

But he's born into a world of absolute monarchy. Tell us a little bit about Lafayette's origins. What are his early years? Lafayette is your prototypical rich orphan.

Mike Duncan: His dad dies when he is two, uh, so he never knew his father. He knew his mother and loved his mother, but she died, uh, when he was just a kid, when he was like, I forget if it was 11 or 12 years old and I get hazy on which month she died in.

Um, but he was like 11 or 12 when she died. And he was the only living male. At that point, not just to all of the fortunes that come in from his father's side, but also all the fortunes that are gonna come in from his mother's side. He becomes the heir of about three or four different noble houses where people start dying and he starts inheriting everything.

So by the time he's like 13 or 14 years old, he's like one of the richest people in France. So the Royal family has probably gotten beat in, in like raw wealth, but he's, he's in the top 10. Like if there were some friends, if there was some ostial regime Forbes list, his 14 year old kid is like on the list.

And so that makes him obviously one of the most eligible bachelors in France. He's 14 years old. He's single. He has no brothers and sisters. He has no parents. He's loaded to the nine. He marries into, he met his wife. Adrienne is the daughter of one of the most powerful families in France. The Noailles who are probably in terms of their wealth position and influence are second only to the Royal family themselves.

It is hard to understate how crazy important than know. And Lafayette marries into this family and that sort of that's his early childhood. That's where he comes from. But I think critically he's born and raised out on the periphery of France. He comes from a place called shoving yak, which is down in Overn.

He was, uh, his family were rustic soared Nobles who lived in the provinces. He himself didn't even move to Paris until he was, uh, uh, I think 10 years old. When he marries into this family, the Novi family, he's rich, he's young, but he doesn't, he wasn't born and raised in this environment. And so when he, he, when he enters this world, he doesn't really fit in with it.

And that becomes sort of like the crux of how he winds up, popping out the other side and running away to join the continental army is the sort of the, the position that he was in. He was not comfortable. With where he was sitting in Versailles. And as you say, one of the most opulent places on earth.

Jim Ambuske: Yeah. That was one of the more fascinating things I've found in your book. I mean, as you say, here's a guy who was loaded to the nines. You know, unfortunately death plays a huge role in helping them acquire that wealth, but he's on the periphery and there is a real class dynamic. And I have this thought in my head, I've got a book it's almost a kin to the perception here in the United States that a Southern accent is somehow an indication of intelligence.

And it seems like there is something similar going on here at Lafayette. Where is he, he's very much seen as a kind of provincial in Paris society or Parisian society. And he doesn't necessarily fit in very well.

Mike Duncan: He very much was. And, you know, I don't come from any rarefied air in terms of like what we would consider, like, uh, the un-American aristocracy.

There are codes of conduct, manners, and assumptions that go on with like, Old money in Boston or New York or something like that. Kinda like the old, the old, uh, Brahmins, wasps belief, like the, you know, like the boarding school stuff that like, you know, like Salinger was writing about. If I tried to walk into that world is just some kid from Seattle, Washington.

I would be making a fool. I wouldn't know what fork to use. Right. I wouldn't know what dances to do. I wouldn't understand like the music. I talk about this in the book that from a very young age life at Versailles was a performance. It was incredibly theatrical in what you wore in how you walked, like literally how you walked, uh, how you laughed when you laughed, how you discuss things.

And as you said, like the accent itself, like he was not born with a Parisian accent. He comes from Chavaniac. And so it's very noticeable to him. And to everybody else that he's awkward in this setting, he's a teenager. He like any teenager, you know, you're trying to fit in with a bunch of rich kids.

Sometimes it works. Sometimes it doesn't. And for Lafayette, it didn't, it didn't really take.

Jim Ambuske: One of the other interesting things I've found when I was reading your book and this connects back to your work on the history of Rome podcast series, is that, whereas a lot of these elites in France are really interested in Roman republicanism, ironically, and really taken to heart of people like Cassius and Brutus and the great orators and whatnot, strangely enough, right? In an absolute as monarchy Lafayette really likes Vercingetorix the guy who challenges Julius Caesar ultimately defeated by Caesar. But he leads the Gallic tribes against Caesar. And what explains that? Why does he identify with Vercingetorix, as opposed to these other, I guess you could say more mainstream classical figures.

Mike Duncan: Uh, this was, this was one of the things that I, and, uh, sort of in, as you write a book like this, you come across certain little things or anecdotes that me as the author find utterly delightful. And I find this delightful because of all the work that I did in the history of Rome. And I have spent so much time in Roman history that when you talk about this generation of French revolutionaries, as you said, it is very strange that the curriculum was read Plutarch, read.

read all these people who lost the virtues of Republican. And the concepts of citizenship, as opposed to like being the subject of an absolute regime, they sort of knew it at the time. Like the kids who were being raised on this stuff would look back later and it's like, you know, you, you taught us nothing, but like Brutus and Cassius were the good guys.

What did you think was going to happen? That's like Lafayette's contemporaries. Yeah. They want it to be Cicero. They wanted to beCato. George Washington's favorite play is Cato, or this is the thing that is like, sort of circulating through the entire. Intellectual world at the time, Lafayette reads all this stuff.

Yeah. And he, he doesn't follow the Romans. He gets super into Vercingetorix because like I say, he comes from Auvergne and Auvergne is named after the Arverni. They Gallic tribe that produced Vercingetorix. Right. He was, uh, he was an overnight chieftain who then, uh, unified the Gallic tribes to make their last stand against the conquest of Caesar.

And I really liked that. As an insight into where Lafayette is at, not as an old man, once he's had a chance to sort of consider everything and rewrite his own history, but what he's thinking. As a teenager, he clearly identifies with the sort of, uh, the freedom fighter icon, right? We know this is a, this is a standard sort of trope of TV and movies and novels, the freedom fighter standing up for his people against, you know, some kind of encroaching enemy and that's who Lafayette wanted to be.

He didn't think of himself as a patrician Republican in Rome. He thought of himself. As, as a rustic individual who is going to stand up for freedom against some kind of encroaching power. And so this, this fits this, I mean, this is like hand in glove. Like then, then now he's looking over at the American revolution, American war of independence.

And he sees, I think something like that playing out. And I'm sure these things are connecting in his mind.

Jim Ambuske: Yes. Tell us a little bit about that. How does he make those connections? How does he get involved in the American revolution in the first place? What, what appeals to him about.

Mike Duncan: The setting for all of this is that when the American war of independence breaks out in 1775, Europe is quite unusually going through a period of great power, peace, the last great war.

There's nothing Europeans love doing more than fighting wars with each other,

Jim Ambuske: especially the British and the French.

Mike Duncan: Yeah. Yeah, sure. And, and, and yeah, and the, and the Prussians and the Austrians and the French and the British, like there, you know, that's what they do at this point. There is great power peace, but over in the new world, over in these British colonies have decided to rise up and revolt against the British crown and what this means.

There's a press, right. There are newspapers. There are letters, uh, people comment on global events, world events, current events, exactly the same way that we do today. And everybody in France was well. That these people had gone into revolt against the British, the British are the enemies of the French. So [00:15:00] to have these colonists, trying to throw off the yoke of their colonial masters and maybe humble the British empire and take the British empire down a peg, the French love this..

They're like, this is awesome. Then there was a, there was a rage for Liz's soon Jones, right? Uh, where people are, they're playing a card game called Boston, you know, hairdos are like supposed to be calling upon, uh, what's happening in the new world. So it's something that is, that is in the air that people are discussing and talking about.

And Lafayette as a young, adventurous minded, ambitious kid who's not feeling at home where he is, and then there's other stuff that happens that sort of moves him even further in this direction. He sees this as an opportunity to go do something great and cool and fun and make a name for himself that is also simultaneously fighting for these ideals that are also floating around in the same.

Liberty equality, citizenship rights, these notions that have already, if you know, for a generation been floating around out there, these two things now combine, and this, this is like the perfect opportunity for him. And he does you know, he does not miss his opportunity. He. What does he expect to find once he gets in America?

Jim Ambuske: And what's the reality he encounters? Well, Lafayette was a rich 19 year old French aristocrat with a head full of visions that everybody in America. Was a, a freedom loving yeoman farmer. Um, everybody is, uh, treats everybody else with, with absolute equality. All they love is Liberty and freedom. And all they're trying to do is achieve Liberty and freedom.

So it's, it's this very, very sort of, sort of superficial quasi utopian vision that he has for what these people are doing. And even when he lands, you know, like this is obviously Hero of two worlds, I'm very sympathetic to Lafayette, but I'm not going to skip over the warts stuff, right? This is not a, I'm not hagiography in any meaningful way.

So when he comes over and he went, where's the first place he lands South Carolina, his first night in America. Where does he stay? Stays at the, he stays of the home. A guy had called a major UGI who was a rice plantation owner and a major in the South Carolina. Slave owner. So Lafayette spends his first night in America, honestly, a plantation.

And then as he's traveling up through the United States, from South Carolina to Philadelphia, to turn in this commission that he has received in the continental army, he's riding back home and he's saying, oh, this is such a great land of Liberty and republicanism. Everybody's free. Everybody has land everybody.

You know, everybody has treats each other. Well, everybody has a Negro, right? There's no. And you're like, dude. This is a very interesting line because there, there are two versions of Lafayette's letters that got printed one immediately after his death, by his family. And then a second, like very scholarly compendium that happened in the late 1970s and early 1980s at Cornell university.

And they went back through the manuscript and they could find the place where somebody in Lafayette's family had struck that line. From his letter when it was originally published back in 1837, because by that point, you know, Lafayette did figure out very quickly, like slavery and Liberty are in fact incompatible, but when he first gets there, he, he has this incredibly rosy picture.

But over the course of his years in the continental army, going back to France, coming back to America, going back to France, coming back to America from the wheels, do churn. In a real way for him. And so he's writing and saying that stuff in 1777 by 1783, which is just a couple of years later, he's he's by now writing letters to Washington and Jefferson saying like, we got to free, we got to free the slaves.

We cannot do a project of Liberty that continues to allow for enslavement of African people. So he does get there and he gets there by encountering the reality of life in the United States life in the colonial United States. It wasn't all rosey. And then also the relationship with the native Americans.

This is another thing where we're Lafayette is encountering these people and has kind of the standard issue. European notion that these guys are like, they're like children, you know, he has this noble Savage mentality about them, but they are children, the untouched by the, you know, the corruptions of civilization, but definitely.

Mike Duncan: In need of paternal care, but it'll be fine because the United States and the native Americans that causes the same, we're all, we're all in on the same project. And none of that is true, right? I'm, I'm reading Lafayette saying these things and I'm like, Nope, buddy, that is also not true. So it takes him years and years and years to work through some of this stuff, but he's always working on it and I do admire him for that.

Jim Ambuske: Yeah. That was one of the more jarring lines of the book. As you say, He's traveling up the seaboard he's commenting on the quality or the perception of the quality. And then he has this line about quote unquote Negroes. And I think I actually said out loud, like what?

Mike Duncan: Yeah, no, I did too.

Jim Ambuske: And then I don't think I actually knew this.

I think I actually learned this from your book, but it looks like that he actually owned an enslaved person for a very brief time during this period. Is that correct?.

Mike Duncan: Yeah. Well, I mean later after it becomes an abolitionist, of course he winds up owning many slaves and as a part of a failed experiment in emancipation.

But yeah, very, very initially what happens there was a guy called Brice who traveled over on the boat with Lafayette and this collection of French officers. And this guy was acting as a, kind of an interpreter for Lafayette. And while they were traveling up, they pass through Maryland and this guy bought Lafayette.

A slave boy that's. I mean, that's what it is. Like we know how much he paid the line item is just a slave boy. And then he gave it to Lafayette sort of as a, like a welcome present. And also, you know, you're going to need a servant. Right. And in Lafayette's mine has happened just now, is that he's been given a servant.

He's been given a servant boy a page. This is a very normal thing in Europe. He's not really processing. Is going on. And what is transpiring here that he's now the owner of a person, as opposed to the master of a servant, which is a very normal thing for him. This kid is clearly with Lafayette for about a month, maybe six weeks in Philadelphia, and then is never heard of.

We don't know if he just got handed over to somebody else. There's no bill of sale at any other point. You certainly don't hear him mentioned after Brandywine up to him getting wounded at Brandywine. There's clear references from people he's talking to that this kid is like basically running errands for him in Philadelphia.

And then we never hear from him again. I don't know what happened to him.

Jim Ambuske: That's fast.

You know, I wonder if he absconded to British lines as several of Washington sun slave people do that over the course of the war Tarly possible. Well, speaking of Washington, I want to talk a little bit about the beginning of their relationship.

And speaking of times, when I made a verbal comment by reading your book, I had to laugh when I read the bit about Washington, really not enthused about successive waves of French officers coming over. I mean, he's basically like why are these French officers? Don't send them to me. I don't care. Which knowing how important the French become the revolution.

It's kind of funny, but Lafayette somehow becomes the exception.

Mike Duncan: The French officers that George Washington and the second continental Congress had been dealing with up to that point were. In effect mercenaries from Europe, as I said, just a minute ago, you know, this is an era of European peace. So if you are a European officer and you're a professional soldier, you don't have a job right now.

Like you don't, you don't have a way to apply your trade. You know, you've been trained to, to fight wars in Europe and suddenly there's no wars to fight. They're getting the news too. They know that there's this conflict that's happening over in the new world, where there are these sort of rustic, Anglo farmers, amateurs in the art of war.

And we're trying to overthrow, they're trying to beat the British army and the British Navy. Like that's not something that you can just do easily. So I'm going to go over there. I'm going to serve, I'm going, I'm going to get a commission from these people. But the thing is all the people, all the freshmen, especially who go over there.

They're like" I was a captain in some army, so you're going to make me a general, right? I'm going to be like a field marshal. Like I'm going to be above every single other officer in the continental army. I'm going to come in and I'm going to, I'm going to be, I'm going to Lord it above you. I'm going to teach you how it is because I think you're stupid."

"I'm only going to speak French because educated people speak French. And if you don't speak French, then obviously you're uneducated and you need to come to me and you need to learn French so you can understand me rather than having me learn English so I can understand you." And this is going on for months.

And then ultimately like, you know, a couple years where these guys just keep showing up, most of them are liars. You know, most of them are like either they're runaways, they're drunks, they're AWOL. There was a bunch of officers down in, in the serving in the Caribbean, in the French colonies, in the Caribbean who their senior officers were just.

Writing these glowing letters of recommendation for their very worst officer, so they could get rid of them. I got this piece of paper, it was like, I would fought in 50 battles and, you know, I was a field marshal and it's like, dude, it's just because like, he was the worst duty. Always, always fallen asleep on century duty.

And so let's send him up there and be like, Oh, the one other thing is all of them were demanding like, oh, and I want like a million dollars a week. Right? Like all of them were there to make a fortune. They were soldiers of fortune looking to make a fortune Lafayette. On the other hand, Lafayette shows up.

He does none of that. Number one, when he says he's a French marquis who knows the king and queen personally, he's not lying. Benjamin Franklin backs this up with a letter and says like, this dude is one of the most well-connected people we have, as I said earlier, he's in the Noailles family. Right. And everybody knew what that meant.

This is not something that would have been like, oh, who were the Noailles? Everybody knows who they are. And then Lafayette is also teaches himself English. He, he had learned some English. He spent most of his time on the boat, learning English when he gets to the United States, he's trying to use his English.

This is an incredibly endearing thing to do to everybody that he meets. And so when, when he shows up, they're like, okay, you're, you're really nice. And he gets to the second continental Congress. They do try to brush them aside. At first, they're like, no, we're done with French officers. And he's like, but look, I plan on paying my own way.

You don't have to pay me a salary. I will speak English. That is fine. And then he also comes with a certain humility, uh, when they first meet, like within days of meeting Washington is showing off. The continental army and saying like, I, I mean, I know you're from Europe, so this is not exactly what a European army looks like.

And I apologize for that. I'm quite embarrassed. And Lafayette is like, well, I didn't come here to teach you how to do anything. Like I came here to learn from you. I think that little moment right there is probably the first time that Washington probably does a double-take and it's like, wait, what did you just say?

Like, like you're, you're here to learn from me. You're not here to like, I don't have to deal with your arrogance. I have to deal with you wanting to sort of be my protege. Okay. I guess I'll think differently about you. And then things like that. Just keep happening on down the line. And Lafayette does become the exception to the rule.

And then there are others, right? Once the war really gets going, they're French officers and German officers and Polish officers who come over and we know them all, they served with distinction. They were absolutely integral to the functioning of the continental army and its success. Casimir Pulaski. uh, Kościuszko uh, De Kalb, uh Von Steuben.

Like all of these people do ultimately become part of the backbone of the continental army. So, and Lafayette is a part of that, part of that shift, bringing in like the good European officers that he's at the thin end of the wedge on that.

Jim Ambuske: Do you think that Washington saw something of himself in Lafayette and Washington as a young man in his very ambitious, arrogant in ways that I think are similar to Lafayette, it sounds like, but he does mature into the figure that he does become.

Do you think Washington saw is similar spark in Lafayette?

Mike Duncan: Sure. I think there are two things that, again, that, that merge in Lafayette is an ambition to do great things, right. Which obviously Washington can identify with Washington, always had a desire to do great things and be a great person. Setting aside all the critiques that we can levy on the hypocrisy of George Washington, George Washington, at least for himself considered himself an idealistic person who has a sort of a nobility of spirit.

There are virtues that we are trying to achieve here, like accomplish and embody beyond simply winning a battle or winning a war. It's a bigger project than that. And that's, Washington's conception of the continental. Independence, the American Republic, Lafayette exhibit a lot of these same qualities, you know, he's also in it for more than just being a soldier of fortune or being a mercenary.

And he repeats all of these things and says all the right things that Washington kind of wants to hear. And then of course, the other thing is very early, shortly after Lafayette shows up, we have the battle of Brandywine in the battle of Germantown, which, which Washington's army sort of loses and then there's a stalemate, but the British capturing Philadelphia. Meanwhile, up in the north Gates is winning the battle of Saratoga, which is of course, pivotal to the war effort. And the first, really big victory that, that the continental army had had, which Washington obviously did not oversee. And there was a little movement, a very small movement to replace George Washington.

And w without barely even knowing each other, Lafayette is writing these letters to Washington saying like, yeah, but I'm going to back you to the hilt. If anybody tries to replace George Washington has, has had of the continental army. I will tell them I will take me my money, my connections to the French court, and I will quit and go home.

So in terms of what does Washington see in Lafayette that endears Lafayette to him? Washington is also somebody who prizes loyalty, especially loyalty to George Washington. He really likes people who like Georgia. This is a true thing about many people, but certainly in that time and place to hear that steadfast we're in this together.

And you're the leader, Washington loves this. And by this point, I mean, this is within months now of meeting each other. I think this is when, like the father, son dynamic really starts to sink. Lafayette goes on to become a field commander during the war. But I want to ask you about something you just touched upon, which is the significance of Lafayette's influence back home and marshaling French support for the American Revolutionary War.

Jim Ambuske: We touched on Saratoga a little bit, that it had a direct impact on the treaty of Amity and commerce and the Alliance treaty of 1778, but is Lafayette playing a role back home to encourage the government to get behind this revolution in a more overt and sustained way?

Mike Duncan: Absolutely. And you know, this book is not going to argue that Lafayette was the secret driver.

Uh, you know, all, all these myths about Saratoga and Benjamin Franklin are just like, no, of course not like we won Saratoga. Franklin was able to take that to Vergennes and Vergennes was able to take it to the king. And that's where official recognition of French support comes into play. Because obviously theyhave been involved in heavy clandestine support for the American war of independence from the very beginning. And the battle of Saratoga is one with French arms, French munitions, French boots, French uniforms, all of which had just recently arrived from France as a result of, uh, the gun running of Beaumarchais, who is our playwright inventor, gun runner, spy, who's himself, just like an insanely interesting tangent that you can go on, but Lafayette's role in all of this.

Is to be essentially like the key mediator between the French and the Americans when the Alliance gets going, because he isn't, he is somebody who is, as we just said, he's now basically a quasi son to George Washington, probably the most powerful person in the independence movement. He is also close personal friends with Henry Laurens, who is at that point serving as president of the continental Congress.

He knows personally, Louis, the 16th and Marie Antoinette personally, the comte de Vergennes, who was the foreign minister at the time, Lafayette is not somebody who is giving advice or mediating disputes or conflicts or making his arguments up through some chain of command. He has direct access to the principal players and the principle players on both sides, trusted.

Right. Vergennes trusted Lafayette, Washington, trusted Lafayette, Louie the 16th, after some cajoling trust, Lafayette, the other continental army officers, Nathanael Greene, Henry Knox, then Alexander Hamilton. He's farther on down the line when they look at Lafayette and they say, okay, Lafayette is going to go talk to the French.

We can trust that he's not going to portray us. And then when the. I want him to go talk to George Washington or to the sunset continental Congress and work some things out. They believe they can trust Lafayette to do that. And so I think that as the Alliance move forward, and if you study the history of the American war of independence and read the book, you know, that this Alliance is very, it is not smooth.

This is, uh, Anglo Protestant commoners who are trying to form a Republic allying with aristocratic French Catholics who work for an absolute Monarch. Like this is not, this is a very strange Bedford. Alliance that's going on here. And the fact that Lafayette was able to bounce back and forth between the principles of the two sides and really keep everybody kind of on the same page, uh, was enormously beneficial to making sure that the Alliance stays intact all the way through Yorktown, which there were many times that the French were going to pull back from it.

Like this is costing us too much money is maybe not worth it. And there were times which crew's probably true by the way. I mean, we don't have to get into that, but probably true. Um, and then also there were times where the Continentals are like these arrogant. We hate these guys, these arrogant jerks who are just messing everything up there.

They're leaving us high and dry they're. They're not doing what they said they were going to do. They're not sending what they said. They were going to send. There were definitely forces on both sides that wanted to pull away from it. And Lafayette just wanted the people. Uh, and he does this then for the rest of his life.

He casts himself in the role of mediator between the French and the Americans.

Jim Ambuske: As he continues this mediation process throughout the course of his life. After the war, of course, he goes back home and, you know, the war was very expensive for France. That has huge implications for what happens there in the 1780s.

What does it take back from the American revolution that shapes the way he thinks about French politics and society, as, um, as things begin to unravel back home..

Mike Duncan: Lafayette emerges from the continental army and kind of leaves his life as a soldier behind for the rest of his life. Even though later in life, he prefers to be referred to as general Lafayette.

He's going to leave his life as, as just sort of a young soldier behind. And he moves when he returns to France, into being much more of a social reformer and a philanthropist and somebody who is going to look at the world and see the things that ought to be reformed about the world, and then use his time, his money, his influence.

He's now an incredibly famous person, right? He's one of the most famous people, both in France and the United States. And he's going to use his fame and influence for good causes. You know, this, this is, again, this is also like sort of a character who we know both in current events and in history. Famous rich person who's wants to do good things and we can often poke fun at that.

But it's also like, it's probably better for rich famous people to try to do good things than for rich famous people to just sit back and be jerks and do nothing with their money. So he's doing that. You know, the question is what about his experience in the Americas feeds into his role as a social reformer.

And I think that we have these two things he wanted to go off and win a great battle and do glorious things on the battlefield for a good cause. And in the United States, he sees. These people who are trying to reform their system of government, maybe they're obviously not going to reform their social system, but he does kind of expect them to reform their social system because he he's has this certain naivete about the economics and personal interests of many of his, many of his best friends in the United States.

But yes, sees the American revolution as a great success. It didn't have to succeed, but a bunch of people through daring and Alon and virtuous selflessness allegedly were able to accomplish a great project that probably nobody would have expected to succeed. And so now he comes back and he sees all these Protestants are being treated like garbage, right? In, in the French Republic. He's met all the, like, this is a big one. Like he's met all of these Protestants now. And he's like, these are, these people are great. There's nothing wrong with Protestants. So like, and so he comes back and he sees basically their religious brother and being treated like crap in Ancien Régime, France.

And he's like, I want to help the Protestants, I want to help the poor. He gets really into abolitionism, you know, he's he writes a letter to John Adams who's then at that point, ambassador to Britain saying, I want you to send me a creative books of every single thing that has ever been written on the emancipation of slavery, because I want to become an expert in it.

And it is something that I want to pursue, because if what we did over there means anything. It means that ultimately slavery is going to have to be abolished. There's just no other way to conceive. Of this project with slavery continuing. So he gets into that too. And I think this, this stuff does come from the proven success of this kind of daring reform that he believed he had.

He'd participated in, in the American war of independence. And now wants to bring back home to France as part of your journey through this project, you actually traveled to France. How long were you there and what did you find. Oh, I didn't just travel to France. I moved to France. Yeah, my family and I, my, uh, myself and my wife and my two kids who were, gosh, how old were they at the time?

Six and two, I think. And we lived in Paris for three years. I only just moved back to the United States, maybe four or five months ago. I wrote and researched this entire book while living in Paris while living in France. And that experience alone. Being basically an ex-pat in a different country is of course, you know, in a million different ways of transformative experience, but does also, I felt like does give me a certain insight into what, what his life was like, because obviously he did this kind of same thing.

He just picked up and moved to a foreign country, had to learn a new language, had to fit in with people that he had never met before. And kind of, and kind of a different culture. Like how do you go about this? I think there's a bunch of different experiences. Like. That informed the writing of the book.

And of course, being in the places like the fact that I could go down, uh, there's going to be some huge tumultuous events, uh, in front of the Hôtel de Ville in the French revolution. So I can just take my laptop down there and I can sit in that space and write. This piece of the book while sitting in the place where it happened, there's something sort of a magical about being able to do those kinds of things to not just be, and which I, I spent a lot of time in libraries, of course, too, but being able to actually inhabit the spaces that he inhabited and made the book so much better than it might otherwise have been.

I think I would have written a fine book either way, but I think it really gave it a little something extra.

Jim Ambuske: Well, I think it really speaks to the important point that sometimes it's necessary to inhabit this space is where your characters lived. It's hard to describe a landscape and urban space, the emotions, someone might've felt without actually having been in that area.

It's one thing to write about how hot the sun can be here in Virginia in the fall. But in my case, I write about Scotland and the American revolution in the fall is very different in the Highlands that it is in Virginia. And unless you've been there, it's, it's harder to communicate. What someone might have been thinking or feeling in a particular moment, unless you've actually been in that land.

Mike Duncan: I agree with that a hundred percent. And like, going back to the history of Rome day is one of my favorite of all of those ancient writers is Polybius and Polybius is among other things like amongst the first truly you would call like a professional historian who had professional standards about how to use sources, how to think about sources, how to think critically.

We're not just here repeating stories that we've heard, like think critically about what you're reading. Like. Hmm. Okay. So somebody wrote this, what maybe was their interest in writing it? And another thing that Polybius is asks of historians is go to the places that you're writing about. Walk through the terrain, walk through the geography.

I will just admit this, that I got dinged a little bit on the battle of Brandywine, because I have personally not walked through the battle of Brandywine field. And I think I exaggerated a little bit, the tilt of the Hills. I got an email from somebody who was like, I live around here and that's not exactly what it looks like.

And so I think that that's true, you know, you can't visit every single place that you're going to go to. But I think that in the main, I think that that right there comes from the fact that I'm imagining something in my head instead of standing there and doing it. And when you can stand in those places and do those things, yes, it becomes very powerful and very true.

Jim Ambuske: Well, next time you're back this way about a floor or two floors above me is a collection of revolutionary war maps. And I, I think we have a battle of Brandywine mat in there, but nevertheless, we've got a bunch of Lafayette maps the next time you're back this way.

Mike Duncan: Did the maps, that's the thing, right?

Like you can look at, you can look at maps, but as we're just talking about, it's one thing to look at a map and which I had, I had plenty of maps of the battle of Brandywine. I knew where everybody's moving. I can draw a picture of, uh, how they got outflanked. But have I ever actually been to the battle of Brandywine field?

No. And somebody who lives about a mile away from there, let me know it. You know, nobody's perfect. Well, it just proves the point. The local history is in fact important, so important. Oh my God. Yes.

Jim Ambuske: Tell us a little bit about the relationship between writing books and your podcast work. There are two different genres, but I have to imagine there is a connection or relationship between the two.

Are there lessons you learned from your podcasts work that you then translated into your first book. And now this second?

Mike Duncan: Sure. The, and they are different mediums. And basically what the podcast, every single week, I have to write about 4,000, 4,500 words about whatever the topic of that week show is. And I have to be able to move quickly through synthesizing the information, writing paragraphs, editing those paragraphs and getting it out the door.

So the one big thing here is that in terms of my work life, I know what it's like to synthesize. Right. And. Information, I don't agonize over putting out words. Right. So I I'm, I'm able to take that into our gargantuan task that is writing a book, writing a book. On the other hand, I don't have that weekly deadline where I put out an episode and then I move on to the next episode.

And then I move on to the next episode because all through the history of Rome and all through revolutions, if I had the opportunity to go back and say like, oh, Really I should have introduced Mirabeau about three episodes ago or here's something that I really should have brought up earlier, or here's something that I really, I talk a lot about right now, but really nobody needs to know about this for like another 17 episodes. I don't know why I wrote it. Now, when you write an entire book, you can then look at the totality of the. And begin to move ideas around and begin to play with how the entire structure fits together and create one complete and total package that flows in the way that you want it to flow from beginning to end and have the things introduced in the moment that they need to be introduced to hold back.

We needed to hold back and to go forward when he needed to go forward. And that becomes different. I can go back in light of what I wrote on page 430. And look again at page one and say, am I saying the things on page one that are going to be feeding into page 430 with revolutions and with the history of Rome, when I was doing that, that is serialized narrative writing I'm channeling Charles Dickens when it comes to writing. And I'm just going to, I'm going to write a chapter and I'm gonna write a chapter and I'm a write a chapter. And, you know, if it meanders and sprawls and I have to like go back and verbally correct things, that's how it's going to be, as opposed to writing the book, which I can, you can just craft it so much more.

Jim Ambuske: Having done all this crafting and having done on this signposting, what do you think Lafayette's legacy.

Mike Duncan: He is really in a major way, a living embodiment of the ideals and the ideas that were produced by this thing that we call the age of democratic revolution. If you're going to put a label onto this period, You asked me, I think it starts at the end of the seven years war, which is in 1763.

I think you can mark it at 1775 because that's a very famous date, even 1776, because that's a famous day, but really everything's getting gone by 1763 and then it progresses all the way to about 1830. And you have almost a single revolutionary event that consumes the entire Atlantic world with different theaters geographically in different theaters in temporal terms. So you have the American war of independence. You of course have the French revolution. You also have all of Spanish American independence happening at this time. Guys like Simón Bolívar , uh, José de San Martín Francisco Miranda, they're all in this same world. Like they're writing letters to each other.

They're working off of the same ideals. They're looking at Washington and the French revolution. We have the Haitian revolution erupting in the middle of all of this. One of the most important revolutions that's ever taken place. And what is sort of the lasting legacy of that entire revolutionary moment at a minimum?

It's the, the north star of Liberty and equality that people ought to be free and people ought to be considered equal. Have we achieved these ideals? No, of course not. We have not. You can't look at the world today and say, this is when we achieved Liberty and equality, but I do believe it is when we achieve the idea that this is the thing that we're aiming for.

And Lafayette was always aiming for those things. From a very young age to a very old age, he was trying to achieve this. He was not a tightwad. He spent his money on this. He went broke on this project. He spent his time, his money. He literally risked his life. Many times he was a legitimately courageous person.

Both on the battlefield and in politics, if he believed something and he walked into a room, knowing that everybody in the room disagreed with him, he did not tell them what he knew. They wanted to hear. He told them what he believed, which is a very courageous thing to do. And I, don't not all of us. I don't even know how much I have the ability to just go in front of a room full of incredibly hostile people and tell them to their faces.

You're the people that are the problem here. But I think that's, I think that's what it is. You look back at him, he is a living avatar and believed himself as such like he presented himself as a living icon of these ideals that he believed in that I think we're still aiming for and are still virtues.

You know, there are other virtues that I don't think that Liberty and equality in the sort of in the liberal sense of the term are the only things that we need to be doing in society, but they're not sufficient ideas to create, adjust in good world, but they are certainly necessary conditions for adjusting.

Jim Ambuske: More conversations after the break.

Jeanette Patrick: Hey everyone. I'm Jeanette Patrick from the Washington library center for digital history. When I dive deeper into Lafayette story, head over to George Washington podcast.com to see a hand drawn map of the 1778 battle of Monmouth made by Lafayette, the personal mapmaker just after the battle. And now back to the show.

Jim Ambuske: Mike, what book you're reading right now?

Mike Duncan: I am reading about 20 books right now. I am constantly reading books. I'm reading books about the Russian revolution for my work. I am reading books for pleasure. I'm actually sort of bouncing back and forth between two books because I am, I'm ashamed to admit that all through my schooling high school college, and I studied political theory.

I never read anything by W. E. B. du Bois. I even took a, uh, a history of sociological theory class in college. I read Emile Durkheim. I read Marx. I read Weber. Right? I read all of these guys. Nobody ever put W. E. B. Dubois in front of me. So I, at the moment I am reading both, uh, his book about reconstruction and a Souls of Black Folk. Which are both sensational books. I, I'm not being groundbreaking in any way by saying this, but you know, it's not like, oh my God. I discovered, you know, I discovered somebody nobody's ever heard of before, but for me, and this is, this is a process of like, you always have to keep trying to learn the things that you.

Learn before, or, or to break the ground that you just had never broken before. And I, you know, there's a certain degree to which you get older and you get embarrassed about the things that you didn't know. And so maybe you don't ever want to engage with them because you don't want to acknowledge that.

Really. I should have read this 20 years ago, but it's so good because I re I, you know, you read Marx and you read Weber. I talk about them because they're amongst the founders of sociology and Dubois is as well. Those guys are incredibly dense and incredibly dull in terms of their writing. Whereas Dubois is like, dude, the guy is like a sensational writer.

So if you want to get into sociology and you want to read some of the most pressure and observations that have ever been made about American society and find them delivered to you with incredibly lyrical prose, the voice he's really good at it.

Jim Ambuske: Yeah. Amen to that. So who's the author you most admire?

Mike Duncan: There are many authors that have inspired me over the years when I got started on this project of the history of realm and revolutions, like who were the people that I look to a big one is a, this woman named Veronica Wedgwood, who was a British historian, who is also, you know, I I'm in many ways, I'm a writer before anything else? Right. I come into this as a writer, who's writing about history. So I have a great deal of admiration for, uh, the prose, stylings of certain writers and Wedgwood. She writes better clearer than anybody. I think I've ever read. You know, when we're talking about like north stars that we're aiming for, but we don't actually achieve, I'm aiming for her. I'm never going to achieve it. And then the other one in that, in that mix is. Right. She's also in that same vein. And you know, like as you read them, they come out of like the mid 20th century. And if you want to have an intellectual conversation about like where they were as historians and where you can critique them and where you can't critique them, I'm happy to have those conversations, but in terms of their writing and their ability to convey incredibly complicated information in a sparkling prose, which is something that clearly I'm trying to do those two are going to stand up there as a great heroes.

Jim Ambuske: Yeah, that's another great lesson that if you want to become a great writer, you got to read great writing and read it relentlessly. What's the most exciting document you've found over the course of your research?

Mike Duncan: There's two also I'll say two from the Lafayette book, because I got to go to Cornell university for like two and a half weeks.

Cornell university, long story short has one of the largest caches of Lafayette documents in the world. And so I got to go there for two and a half weeks. I was rifling through documents. These are the letters. The literal parchment that Lafayette is drafting, like say on the boat after he's run away from home and he's writing back to Audrey, I'm like, these are the letters.

She kept the letters. And so I'm holding these in my hand and this is very special, but there are two that are in here that I, that I got to mention. One is fun and one is bad. The bad one, we'll start with that. One is the manifest of the slaves that he owned in 1780. They asked the manager of this, uh, plantation that they had bought in French Guiana to sort of send them an itemized list of all their property in that sort of bundle of papers about the itemized list of property is the itemized list of the people that they owned, uh, whom there were 79.

One of them was an old man who was blind. The youngest was a, was a child. I think she was maybe two or four years old. I forget. But so to hold that in your hand, this is not something that's. [00:50:00]I would not say this about biographers of Lafayette, like today. Like there's no contemporary biographer of Lafayette who's living right now, who not only not going to deny that, but is happy to talk about it.

But if you go back through sort of the historiography of Lafayette, this is not something that was talked about for about 150 years. I think it's really important. I think it shines a very interesting light on a human being who tried and failed to do something. That's when you know you hold that, you're just like, okay, you're the nice one that was in, there was a, his daughter on Anastasie was like six years old and, uh, wrote a letter to George Washington saying I, it was an interesting, very careful kid writing.

Dear Mr. Washington. I sure am glad you like my dad. We miss him. I hope he comes home soon, uh, which is a very sort of, uh, cute and endearing saying, wow, that's fantastic. Yeah. That's fun. Archives are great.

Jim Ambuske: Oh yeah. I need to get back into some and at the end of the day, how do you hope people remember your work?

It's a weird thing to be like, what do you hope your legacy is essentially? But what I'm trying to do is explain to people in an accessible. What happened in the past. I want people to listen to my work and come away with a broader understanding of the historical events that shaped our world. Because I think that that having that out there in society, having people out there historically literate about their own past and being interested in his.

Is for the greater good. So even beyond sort of the content, right? Like I, I explained to people about the French revolution and I explained to people about the revolution of 1848 or something. Even if I give somebody a quiz about the information that they should have retained from having listened to all of this, I would almost rather have them be like, okay, I don't remember anything, but I walked out of this with a deep love and appreciation.

For learning about history, right? And so I want to go learn more. I want to read more books. I'm curious about things. It's a little bit of the old cliche of giving somebody a fish versus teaching them to fish. And I hope that there's something that's coming out of the history of Rome and revolutions in these books.

I'm teaching them how to love history, how to be engaged with history, how to find it so interesting that you now want to go. For yourself. And if I can, if I can do that, if I can sort of spread that around there, then I believe that I have succeeded in the project that I'm up to. I think the one other thing that I would throw into this is that I have a, I have a great deal of hostility to the notion that people are stupid.

I don't like the way that many intelligent people go around thinking that everybody else must be impossibly stupid. And that if you're going to explain something to it, you really have to dumb it down and talk in very slow, simple sentences. Otherwise the rubes out there won't I hate this. I think that people are way more intelligent than they are ever given credit for.

I think there are lots of people out there who were told their whole lives, that you're not smart, you're not intelligent. And they internalized a feeling about themselves that they can't engage with complex ideas. They can't engage. With sophisticated knowledge or understandings of things, history, philosophy, sociology, science, like whatever people get brow beaten mentally into thinking that they're stupid because that's the way that people treated them every step of the way.

For me, I have never tried to dumb down anything that I have presented. I have always tried to be clear about what I'm saying so that people can understand it, but I'm never trying to dumb it down or treat people like they're stupid, which I think the world could also benefit a great deal from us not treating each other. Like we're idiots.

Jim Ambuske: I second, everything you just said, and I whole heartedly support it. Mike, thank you very much. This has been awesome. Thank you so much for having me. Yeah, that was great.

Mike Duncan

Author

Mike Duncan is one of the most popular history podcasters in the world and author of the New York Times–bestselling book, The Storm Before the Storm: The Beginning of the End of the Roman Republic. His award-winning series, The History of Rome, remains a legendary landmark in the history of podcasting. Duncan’s ongoing series, Revolutions, explores the great political revolutions that have driven the course of modern history. His most recent book is Hero of Two Worlds: The Marquis de Lafayette in the Age of Revolution.